What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

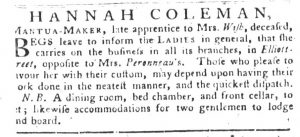

“HANNAH COLEMAN, … late apprentice to Mrs. Wish.”

Hannah Coleman made mantuas. These loose gowns worn by women first came into popularity in the late seventeenth century. In February 1770, Coleman placed an advertisement in the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal to “inform the LADIES in general” that she carried on the business of a “MANTUA-MAKER … in all its branches.” She used a phrase commonly deployed by artisans to indicate that there was no part of her trade beyond her abilities. Accordingly, she pledged that customers would have their garments made “in the neatest manner.” To bolster that claim, Coleman relied on another strategy that often appeared in advertisements placed by artisans, though one usually invoked by men rather than women. She listed her credentials when she named her occupation. Rather than “HANNAH COLEMAN, MANTUA-MAKER,” she was “HANNAH COLEMAN, MANTUA-MAKER, late apprentice to Mrs. Wish, deceased.” She assumed that prospective clients would be familiar with the reputation of the departed Mrs. Wish or at least feel reassured that Coleman had completed an apprenticeship.

Although Coleman adopted a strategy usually reserved for men, her efforts to market mantuas fashioned a world in which women participated in commercial transactions without reference to men. She addressed “the LADIES in general.” She established her connection to her mentor, Mrs. Wish. She even listed her location in relation to another woman, stating that she did business “in Elliott-Street, opposite to Mrs. Peronneau’s” rather than naming male neighbors or using other landmarks. In a nota bene, Coleman did note that she sought “two gentlemen to lodge and board,” but the portion of the advertisement about her activities as a mantua maker depicted a world of women who created their own networks, taught each other, and traded with each other. Women in business tended to publish newspaper advertisements less often than their male counterparts in eighteenth-century America, perhaps because they relied on gendered networks as an alternate means of attracting customers. They participated in the marketplace, but chose means of promoting their enterprises that yielded less visibility among the general public even while generating familiarity among female consumers.