October 1, 1766 This post is from The Adverts 250 Project which is conducted by Carl Robert Keyes, professor of history at Assumption University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Students from Colonial America, Revolutionary America, Research Methods, & Public History courses at Assumption University serve as guest curators for the Adverts 250 Project.

18C

GUEST CURATOR: Nicholas Commesso

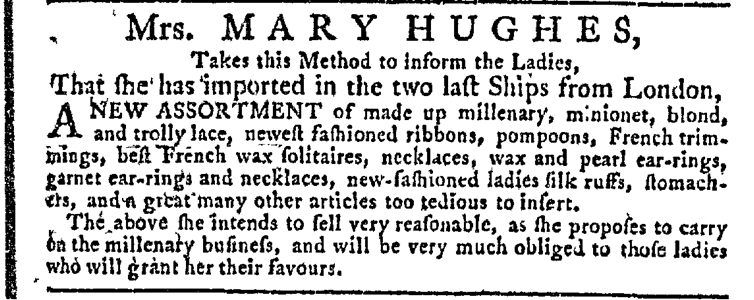

“MARY HUGHES, Takes this Method to inform the Ladies.”

My final post as guest curator introduces the first advertisement by a female entrepreneur I saw in the newspapers I read through. In the Georgia Gazette, Mary Hughes “Takes this Method to inform the Ladies” that she offered an extensive list of goods specifically for women, notably wax and pearl earrings, garnet necklaces, ribbons, “stomachers” (which were “the early ancestors of the corset” and “essential part of a woman’s wardrobe”), and much more. Despite other advertisements catering primarily to men, with a few products aimed for women included, Mary Hughes’ advertisement was aimed solely at women.

This short advertisement ended with Hughes explaining that “she proposes to carry on the millenary business.” A milliner specialized in making women’s hats. Based on the goods listed in her advertisement, it seemed she had all the imported materials necessary to become a continued success! To make that happen, she needed customers. Hughes’ message went on to explain that she would be “very much obliged to those ladies who will grant her their favours.” To me, it seems that this last invitation had a sense of desperation. Perhaps that was not the case; perhaps it is just the formal language that makes it so much different from modern advertisements. Today, I believe this would sound more like a request for charity rather than generating business for her shop.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

I’m both surprised and not surprised that this was the first advertisement for consumer goods and services that Nick encountered during his week as guest curator. I’m not surprised because such advertisements by female entrepreneurs were often rare. They certainly appeared in disproportionately low numbers compared to the number of women that historians know operated their own shops or provided other services in eighteenth-century America, especially in urban ports.

On the other hand, advertisements placed by women were present in colonial newspapers. That Nick did not encounter any others earlier in the week says something about what often comes down to serendipity in the research process. Women did place newspaper advertisements in the 1760s, but they were less likely to do so than their male counterparts. As a result, some issues occasionally featured greater numbers of advertisements by women, while others were completely devoid of marketing efforts conducted by women. Chance, as much as any other factor, explains why Nick did not encounter advertisements by women in any of the other newspapers he consulted this week.

Historians have to work with the sources available to us. We tell the stories that the documents allow us to tell, not always the stories that we would like to tell or that we wish the documents would allow us to tell. Uncovering the history of women in the colonial marketplace and, especially, the history of women in eighteenth-century advertising requires special attention and effort. As often as possible, I select advertisements placed by women to feature on the Adverts 250 Project, both as a matter of principle and as an informal part of my methodology. Women’s participation in the marketplace as producers and retailers was already underrepresented in the public prints in the eighteenth century. I do not wish to compound the problem by overlooking their commercial notices when they did appear.

As a result, I especially appreciate that Nick selected Mary Hughes’ advertisement to feature and analyze. He certainly had other choices for today, but by telling a story that he had not yet told he joined other historians in the endeavor to include women in our narratives of the past.