This post is from The Adverts 250 Project which is conducted by Carl Robert Keyes, professor of history at Assumption University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Students from Colonial America, Revolutionary America, Research Methods, & Public History courses at Assumption University serve as guest curators for the Adverts 250 Project.

“She has employ’d a young woman lately arrived from London.”

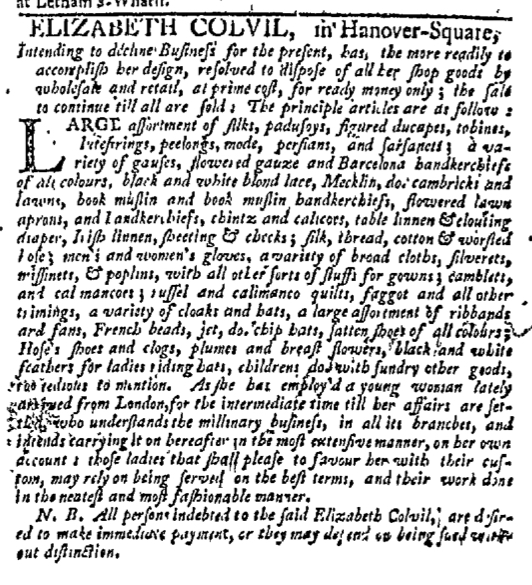

When she decided to “decline Business for the present,” shopkeeper and milliner Elizabeth Colvil announced the eighteenth-century equivalent of a going-out-of-business sale. She “resolved to dispose of all her shop goods by wholesale and retail, at prime cost, for ready money only; the sale to continue till all are sold.” Colvil was liquidating her merchandise, enticing prospective customers with low prices in order to move the process along as quickly as possible.

In and of itself, that sort of promotion distinguished Colvil’s advertisement from many others of the period, but it was not the only aspect of her announcement that set it apart. After listing much of her remaining merchandise and promising “sundry other goods too tedious to mention,” Colvil indicated that she had hired an assistant, a young woman who had recently arrived from London. Her assistant, “who understands the millinary business, in all its branches,” would stay on until Colvil closed shop. At that time, she would pursue the business on her own “in the most extensive manner.” Although Colvil was not selling her shop to her assistant, she was setting her up as her successor.

To that end, Colvil made an appeal to current and prospective customers: “those ladies that shall please to favour her [the young woman recently arrived from London] with their custom, may rely on being served on the best terms, and their work done in the neatest and most fashionable manner.” Colvil voiced a strong endorsement of her assistant, directing the women of New York to patronize her assistant’s shop once Colvil had departed the marketplace.

This differs significantly from most eighteenth-century advertisements in which male merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans indicated the amiable end of a partnership or the transfer of a business from one man to another. In such cases they used advertisements to announce a change in status but did not incorporate an extensive endorsement of the new business or its proprietor.

Elizabeth Colvil probably knew a thing or two about the particular difficulties of being a woman and operating a business in eighteenth-century America. As a result, she attempted to assist her assistant in launching her own shop, recognizing that a young woman, especially one new to the city and unknown to most of its residents, would benefit from establishing a good reputation as quickly as possible. Colvil’s endorsement in her advertisement was the first step. The assistant working with customers was the second. She could build up a clientele, drawing on Colvil’s network of patrons, while the senior shopkeeper and milliner was still active in the business. In this advertisements, Elizabeth Colvil advocated on behalf of a fellow female entrepreneur.