French Fashion Plates 1777

French Fashion Plates 1777 French Fashion Plates 1777

French Fashion Plates 1777

Hannah Coleman, Mantua Maker, South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, Women in Business

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

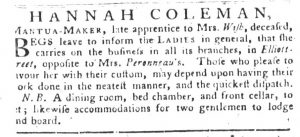

“HANNAH COLEMAN, … late apprentice to Mrs. Wish.”

Hannah Coleman made mantuas. These loose gowns worn by women first came into popularity in the late seventeenth century. In February 1770, Coleman placed an advertisement in the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal to “inform the LADIES in general” that she carried on the business of a “MANTUA-MAKER … in all its branches.” She used a phrase commonly deployed by artisans to indicate that there was no part of her trade beyond her abilities. Accordingly, she pledged that customers would have their garments made “in the neatest manner.” To bolster that claim, Coleman relied on another strategy that often appeared in advertisements placed by artisans, though one usually invoked by men rather than women. She listed her credentials when she named her occupation. Rather than “HANNAH COLEMAN, MANTUA-MAKER,” she was “HANNAH COLEMAN, MANTUA-MAKER, late apprentice to Mrs. Wish, deceased.” She assumed that prospective clients would be familiar with the reputation of the departed Mrs. Wish or at least feel reassured that Coleman had completed an apprenticeship.

Although Coleman adopted a strategy usually reserved for men, her efforts to market mantuas fashioned a world in which women participated in commercial transactions without reference to men. She addressed “the LADIES in general.” She established her connection to her mentor, Mrs. Wish. She even listed her location in relation to another woman, stating that she did business “in Elliott-Street, opposite to Mrs. Peronneau’s” rather than naming male neighbors or using other landmarks. In a nota bene, Coleman did note that she sought “two gentlemen to lodge and board,” but the portion of the advertisement about her activities as a mantua maker depicted a world of women who created their own networks, taught each other, and traded with each other. Women in business tended to publish newspaper advertisements less often than their male counterparts in eighteenth-century America, perhaps because they relied on gendered networks as an alternate means of attracting customers. They participated in the marketplace, but chose means of promoting their enterprises that yielded less visibility among the general public even while generating familiarity among female consumers.

++Turkish+Woman+Playing+Lute.jpg) 1714 After Jean-Baptiste Van Mour (1671-1737) Turkish Woman Playing Lute

1714 After Jean-Baptiste Van Mour (1671-1737) Turkish Woman Playing Lute+Turkish+Woman+Playing+Zither.jpg) 1714 After Jean-Baptiste Van Mour (1671-1737) Turkish Woman Playing Zither

1714 After Jean-Baptiste Van Mour (1671-1737) Turkish Woman Playing Zither+Turkish+Woman+Smoking.jpg) 1714 After Jean-Baptiste Van Mour (1671-1737) Turkish Woman Smoking

1714 After Jean-Baptiste Van Mour (1671-1737) Turkish Woman Smoking+Wife+of+Sultan+Ahmed+III.jpg) 1714 After Jean-Baptiste Van Mour (1671-1737) Wife of Sultan Ahmed III

1714 After Jean-Baptiste Van Mour (1671-1737) Wife of Sultan Ahmed III Charles Jervas (Irish Baroque Era painter, ca.1675-1739) Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Charles Jervas (Irish Baroque Era painter, ca.1675-1739) Lady Mary Wortley Montagu 1725 attributed to Jonathan Richardson (1665-1745). Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

1725 attributed to Jonathan Richardson (1665-1745). Lady Mary Wortley Montagu 1752-54 Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774). Mrs. John Dart

1752-54 Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774). Mrs. John Dart+pvt1st-gallery-art.com.jpg) 1763 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Mercy Greenleaf (Mrs. John Scoally)

1763 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Mercy Greenleaf (Mrs. John Scoally) 1765 Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774) Anne Livingston (Mrs. John Champneys)

1765 Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774) Anne Livingston (Mrs. John Champneys) 1767 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Rebecca Boylston (later Mrs. Moses Gill)

1767 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Rebecca Boylston (later Mrs. Moses Gill) 1769 Artist: John Singleton Copley (1738-1815) Subject: Martha Swett (Mrs. Jeremiah Lee)

1769 Artist: John Singleton Copley (1738-1815) Subject: Martha Swett (Mrs. Jeremiah Lee) 1769 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Elizabeth Storer 1726-1788 (Mrs. Isaac Smith)

1769 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Elizabeth Storer 1726-1788 (Mrs. Isaac Smith).+Catherine+Greene+(Mrs.+John+Greene).+The+Cleveland+Museum+of+Art.jpg) 1769 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Catherine Greene (Mrs. John Greene)

1769 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Catherine Greene (Mrs. John Greene) 1770 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Sarah Henshaw (Mrs Joseph) 1722-1822

1770 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Sarah Henshaw (Mrs Joseph) 1722-1822.+Rebecca+Lloyd+(Mrs+Edward+Davies).jpg) 1770s attributed to Henry Benbridge (1743-1812). Rebecca Lloyd (Mrs Edward Davies)

1770s attributed to Henry Benbridge (1743-1812). Rebecca Lloyd (Mrs Edward Davies)__Margaret_Cantey_(Mrs__John_Peyre)__Gibbes_Museum_of_Art,_Charleston,_South_Carolina.jpg) Henry Benbridge (1743-1812). Margaret Cantey (Mrs. John Peyre)

Henry Benbridge (1743-1812). Margaret Cantey (Mrs. John Peyre).+Sarah+White+(Mrs.+Isaac+Chanler).+Gibbes+Museum+of+Art,+Charleston,+South+Carolina.jpg) 1770s Henry Benbridge (1743-1812). Sarah White (Mrs. Isaac Chanler)

1770s Henry Benbridge (1743-1812). Sarah White (Mrs. Isaac Chanler).+Frances+Tucker+(Mrs.+John+Montresor)..jpg) 1771 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Frances Tucker (Mrs. John Montresor)

1771 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Frances Tucker (Mrs. John Montresor)+Winterthur.jpg) 1771 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Mary Philipse (Mrs. Roger Morris)

1771 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Mary Philipse (Mrs. Roger Morris) c 1772 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Abigail Pickman Eppes (Mrs. Sylvester Gardiner)

c 1772 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Abigail Pickman Eppes (Mrs. Sylvester Gardiner).+Catherine+Hill+(Mrs+Joshua+Henshaw).+Museo+Thyssen-Bornemisza,+Madrid+Oceansbridge.com.jpg) 1772 John Singleton Copley ( 1738-1815). Catherine Hill (Mrs. Joshua Henshaw)

1772 John Singleton Copley ( 1738-1815). Catherine Hill (Mrs. Joshua Henshaw) 1773 Henry Benridge (1743-1812). Sarah Middleton (Mrs. Charles Coteworth Pinckney)

1773 Henry Benridge (1743-1812). Sarah Middleton (Mrs. Charles Coteworth Pinckney) 1773 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Rebecca Boylston (Mrs. Moses Gill)

1773 John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Rebecca Boylston (Mrs. Moses Gill) 1776 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Julie Stockton (Mrs. Benjamin Rush)

1776 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Julie Stockton (Mrs. Benjamin Rush) 1780 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mrs. John B. Bayard

1780 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mrs. John B. Bayard 1780 Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828). Christian Stelle Banister and son John

1780 Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828). Christian Stelle Banister and son John 1780s Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mrs Robert Morris

1780s Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mrs Robert Morris 1780s Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mrs Frederick Green

1780s Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mrs Frederick Green.+Lady+of+the+Middleton+Family..jpg) 1780s Henry Benbridge (1743-1812). Lady of the Middleton Family

1780s Henry Benbridge (1743-1812). Lady of the Middleton Family+(1763–1823)+Yale.jpg) 1787 Charles Willson Peale 1741-1827 Mrs. Walter Stewart (Deborah McClenachan) (1763–1823)

1787 Charles Willson Peale 1741-1827 Mrs. Walter Stewart (Deborah McClenachan) (1763–1823).+The+Hartley+Family.+The+Art+Museum.+Princeton+University..jpg) 1787 Henry Bendridge (1743-1812). The Hartley Family

1787 Henry Bendridge (1743-1812). The Hartley Family 1788 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mrs Richard Gittings

1788 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mrs Richard Gittings 1789 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mary Claypoole Peale

1789 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Mary Claypoole Peale